The catch-22 of bicycle infrastructure

“That’s some catch, that Catch-22.”

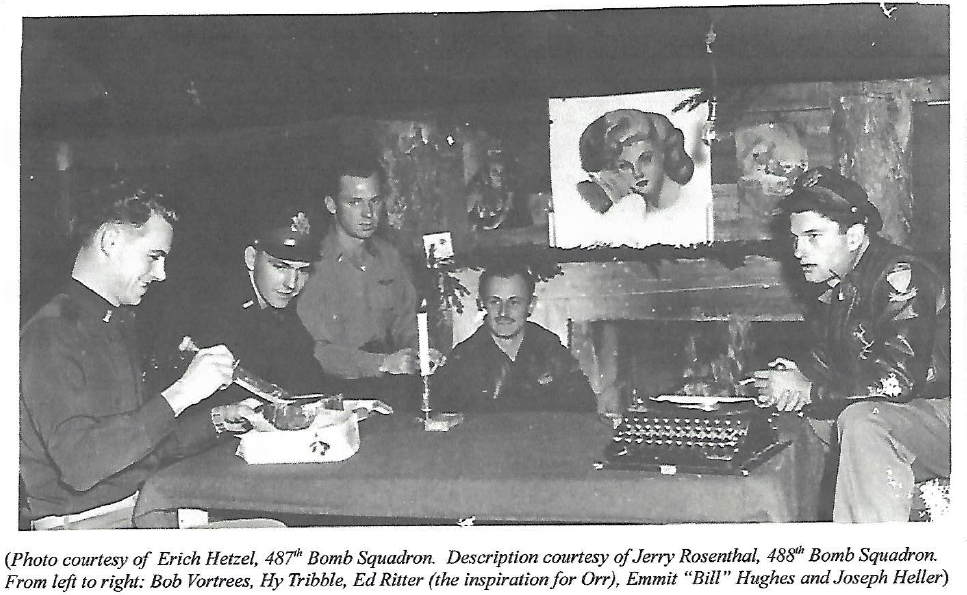

A few years after reading Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22, I learned that my grandpa’s cousin, Ed Ritter Jr., served as the model for Orr, a bomber pilot with a knack for being shot down over water. Heller and Ritter had shared a tent together while serving on the Italian Front during World War II - Heller as a bombadier and Ritter as a pilot. Heller recounted in his memoir, Now and Then, that Ritter was “taciturn, good-natured, soft-spoken, even shy, from Kentucky” and remained “imperviously phelgmatic” despite several unlucky mishaps in combat.

In the novel, Orr falls victim to Catch-22, a bureaucratic rule that kept pilots from being grounded. Orr was crazy because he had to be crazy to fly a combat mission, and thus his insanity necessitated being grounded. But if he asked to be grounded because he was crazy, he was actually sane for wanting to get out of combat and had to keep flying.

Advocates for improving bicycle infrastructure in the United States face a modern-day Catch-22 in how transportation projects are traditionally planned. Transportation engineers are familiar with the concept of signal warrants, which are metrics that determine when traffic signals are necessary at specific intersections. Warrants usually rely on vehicular volumes, just like the most common transportation planning metric: level of service.

This reliance on existing volumes - and even the implicit assumption that a clear warrant is needed to take action - is pervasive across the field of transportation planning. When a new or improved bicycle facility is being discussed, engineers or planners will often conclude that it isn’t necessary because the existing volume of cyclists doesn’t support it.

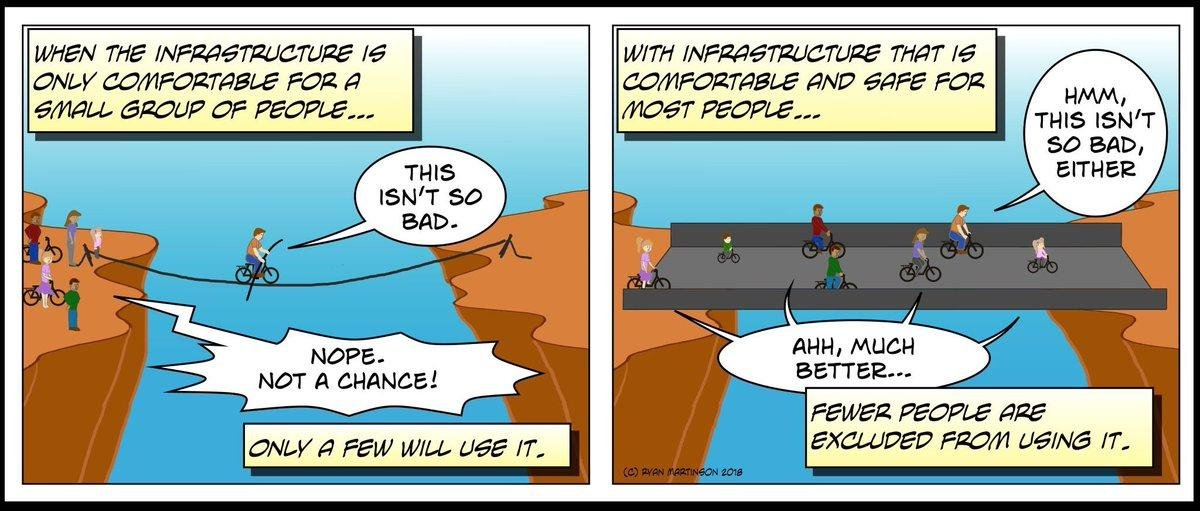

Unfortunately, this conclusion completely misses the fact that no one bikes there because there are no bicycle facilities in place (or they’re of such poor quality that it’s more dangerous to bike there than somewhere else with nothing). This is bicycling infrastructure’s Catch-22, where the only solution to the problem is denied by a circumstance inherent to the problem.

It’s not like this is a new critique. There’s a common joke among transportation planners that an engineer will look at a river and say, “Why do we need to build a bridge over the river if no one’s swimming across?” We need more bicycle infrastructure but we won’t build it because no one is biking… Yet no one bikes because there’s no bicycle infrastructure.

What many European countries already understand (and what the United States fails to) is that a majority of the population could become at least casual cyclists if the infrastructure is right. In the early 2000s, Roger Geller proposed a new typology for cyclists. Geller identified four types of cyclists and estimated how many adults in Portland identified as each type; subsequent research by Dr. Jennifer Dill and Nathan McNeil extended this typology across the 50 largest metropolitan regions in the United States.

Far too often, planners only plan for a small minority of confident and fearless cyclists and assume everyone else won’t bike. However, Dill and McNeil found that over 50% of adults identified as “Interested but Concerned” and only a third identified as “No Way No How.” By designing for all ages and abilities, we can begin to capture cyclists who are interested but concerned and turn our cities into places where everyone can bike safely, comfortably, and joyfully.

In the end, Orr’s experience being shot down allows him to escape to Sweden and Yossarian realizes that Catch-22 doesn’t actually exist. It’s only effective because the bureaucracy claims it does and we believe them. We can, should, and need to build quality bicycle infrastructure without being forced to justify their value based on existing use. We need to remember the voice that Kevin Costner heard in Field of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come.”